Islam: Interview with a PhD in Arabic Linguistics

I recently reconnected with an old seminary friend of mine – Phillip Stokes. Phillip has been very busy since seminary. He lived in the Middle East, predominantly Jordan, for a number of years where he studied Arabic (the language of the Qur’an) along with Biblical and Rabbinic Hebrew, various Aramaic dialects, Biblical Greek, Ugaritic, and Akkadian (Old Babylonian). He didn’t study Arabic just to learn fluency, like some of us did when we took courses in Spanish or French in high school or college, but to also understand its history, development, and usage.

We are living in an era where the Western world and the Islamic world are interacting, intersecting, and in some cases blending together more and more. It has recently become apparent in my life that more work needs to be done on all of our parts to build a more honest and informed understanding both of Islam and of ourselves (sees A Journey into Islam).

For all of these reasons, I am excited and grateful to have the opportunity to pick Phillip’s brain on the topic of Islam – a subject that I along with so many Americans, and perhaps Westerners in general have very little experience or expertise in.

[You can find out more about Phillip on his page HERE at the University of Texas.]

Nathan: Phillip, before we get into the big questions, is there anything you would like to add or that I left out from the introduction?

Phillip: I’d first like to express my excitement for the opportunity to share a bit from my own study of, and experiences with Islam. I think these sorts of conversations are precisely the type that will pave the way to the future we all want to have together – one of dialogue and peace, rather than discord. Other than that, I think it’s important to be a bit more explicit for readers as to what my specialty is, and what it is not. My specialty is primarily in the linguistic study of Arabic and the Semitic languages. I am working on two projects currently. One deals with pre-Islamic Arabic inscriptions from Jordan. We’ve discovered literally tens of thousands of Arabic inscriptions from the pre-Islamic period in recent years, and it’s led to a revolution in our understanding of the makeup of Arabic before the appearance of Islam and the Qur’an. We used to think that the Qur’an, along with some poetic texts, were our earliest examples of Arabic. No longer! The second is a treatment of a selection of linguistic features from the pre-Islamic period to determine to what extent the diversity attested in the early material is represented in later texts. I work with the Qur’an quite a bit, but primarily as a linguist and historian. I have a lot of familiarity with Islamic history and traditions, and I spend a lot of time working on Arabia in late antiquity (2nd – 6th centuries AD), but I am not strictly speaking a specialist in Islamic sciences. For that reason, my take on your questions will likely be different than those who write most of the introductory textbooks with which most of your readers will be familiar.

Nathan: In our previous discussion you mentioned you were not a Traditionalist in regards to how you interpret the Qur’an and I sensed a scholarly rivalry there (Yes, scholars fall into groups on almost any subject of study and somewhat like sports teams, these groups have “rivalries” over their different perspectives). What do you call the group that you are in? What are the differences between the two?

Phillip: It’s a great question. As far as terminology is concerned, we don’t really have a fun name, which is probably due to the fact that not all scholars whom I would dub as “non-traditionalists” share a close perspective on these topics. So in this case it may be more helpful instead to define what I meant by “traditionalist.” I see traditionalist scholars as those who work within the broad framework of traditional Qur’anic interpretation as it was worked out over centuries, beginning in the late 7th century CE (1st century after the Hijra). There is certainly quite a bit of diversity within this broad group – virtually all Muslims and most Islamic scholars throughout history! But in terms of basic assumptions about the Qur’an, they will share the notion that it is the very word of God, delivered to Muḥammad through the angel Gabriel, and is the final and perfect revelation of God to man. Further, they assume certain things about the language itself, which are technical and needn’t concern us here. Importantly in terms of our discussion of translations, they will translate and interpret the Qur’anic passages according to the most widely accepted explanations, which were developed only quite a bit later than Muḥammad’s life. They would not be open to critical re-evaluations of the meanings of passages in the Qur’an based on recent discoveries, historical work that changes our understanding of the nature of, say, the religious makeup of the Arabian Peninsula, etc. I consider myself a non-traditionalist in that I don’t limit myself to specific interpretations based on conformity to Islamic doctrine.

Nathan: If you had to guess, what percentage of Muslims today would you say hold a Traditionalist view of the Qur’an? Are there particular areas of the world where the non-traditionalist’s view of the Qur’an is more influential than others?

Phillip: I would say, based purely on my own intuition (not on a study of which I am aware), that most, if not all Muslims would adopt the basic notion that they are traditionalist. That is, they would all see themselves as being faithful to what they see as the message and teachings of Islam. What’s interesting to look at, though, is how different one’s interpretation of what the Qur’an/Muḥammad etc teaching can be. I would wager that virtually no Muslim would entertain much of what (non-traditional) scholarship is saying about the Qur’an, early Islam, etc.

Nathan: I believe you mentioned that this is a Traditionalist view, but I have read and heard from a number of Islamic sources that the Qur’an was given to humanity for “all times and all places” – to be the supreme guide for ethics, theology, law, etc. What is your take on this? From the Traditionalist’s perspective and from the non-traditionalists’ perspective, does this mean that Islam is inherently anchored in the ethos of seventh century Arabia?

Phillip: Well you’re absolutely right, Muslims do affirm the notion that the Qur’an is for all times and places, and is the final and perfect revelation of God. This is a matter of faith, of course, as is such affirmation of the Bible, Tanaakh, etc. Scholars of course often (though not always!) operate from a position of agnosticism in terms of these claims. Our job should be to attempt to understand these texts as products of their contexts, and leave their ultimate truth claims, or others’ truth claims about them, for members of the respective faith communities to discuss. This is especially difficult when dealing with the Qur’an, though, because so much of western scholarship has been built on the assumption that the traditional Islamic narrative about the Qur’an, Muḥammad, etc is historically accurate. We’re coming to realize more and more, however, that there is a tremendous amount of important material that is absent from the classical sources that changes the way we understand the Qur’an, the message of early Islam, etc. Getting back to a traditionalist point of view, though, an important point here is that there is a difference between “what do we think this text says/means?” and “what does that mean for us (i.e., now in our contemporary context)?” Both are interpretive, but the latter is just as important as the former for understanding what the Qur’an “says,” but it is precisely what is missing from most non-Muslim discussions of Islam. Many Muslim communities, including the “Classical” Islamic age during the Abbasid period, have fully engaged other cultures, adopted from them, etc. In fact, during the classical age, Muslim scholars translated and debated classical Greek philosophy, Syriac religious texts, etc. The big drive to ignore all of this subsequent tradition and get back to the period of the early community (the period of the Rashidun, or “rightly guided caliphs”) has to do with the notion that somehow that gets one to the fundamentals of the religion. A similar notion is found in Protestant fundamentalism today, which is why some of these communities go so far as to reject modern technology in general. It’s a rhetoric that promises reversal of current misfortune (on this topic, see further comments below). Any religious tradition with a sacred text (or set of texts) at its core will always have the challenge of deciding what aspects of those texts (which inevitably reflect their own world) should be appropriated, and to what degree of replication, and which should be jettisoned.

Nathan: You mentioned earlier the “Qur’anic interpretive tradition.” Can you explain this a little bit and its role in Islamic life? What role does this play in the Muslim layman’s understanding of the Qur’an? Does the interpretive tradition ever take precedence over the Qur’an or in practice have the ability to re-write the message of the Qur’an?

Phillip: So what I dub the “Qur’anic interpretive tradition” is the long (almost as old as the faith itself) tradition of scholars and jurists processing the Qur’an and appropriating it for their contemporary contexts. The importance of this body of tradition can hardly be overstated and is a critical piece of the puzzle. Scholars have from early on discussed what passages of the Qur’an mean, as well as what relevance they have to the community, and established (broadly) an orthodoxy of sorts (though in a slightly different way than in Christianity). In much the same way as, say, the Catholic Church has a certain catechism (or set of teachings), various schools within Sunni Islam (not to mention the Shia “denomination”) have developed orthodox and heterodox teachings concerning the Qur’an, Ḥadith, etc. Just as, for Catholics, the Church’s teachings determine the true meaning of the Bible, that is, what the Bible “says,” for many, if not most Muslims, tradition determines what the Qur’an “says.” They of course would never see this as taking precedence over the Qur’an, nor re-writing it, but rather determining the true interpretation of its meaning from false interpretations.

Nathan: I have been told that the majority of Muslims today do not speak Arabic and that even for the ones who do speak Arabic, the Arabic that they understand is different than that of the Qur’an. This would mean that the vast majority of Muslims, even the ones who are reciting it over and over again and memorizing it, don’t understand what it says. They don’t understand what they are reciting and memorizing. How true is this?

Phillip: Well it’s often surprising to note to people that 75% of the world’s Muslims are not Arab and live outside of the Middle East! Those Muslims that do speak Arabic, speak dialects that are very different from that of the Qur’an. The question as to whether or not they understand it is tied to the point I made in reference to the last question. What it means is a matter of interpretation. I mean, there is much vocabulary that is still used today, so it isn’t quite like reading Beowulf for us, where virtually every word is completely opaque. But the stylistics and nuance of much of the language is different enough that they rely on the interpretive tradition(s) they’ve been taught to parse out “what it says.” They, like all persons of faith, engage their sacred text through a certain set of lenses. When I lived in Jordan I would take taxis almost daily (much cheaper there), and it was very common, during the course of a conversation, for the taxi driver (if he was particularly pious) to recite portions of the Qur’an. I often asked them what they thought it meant. Usually they would attempt to explain, and it was often virtually identical from person to person. They would occasionally admit they weren’t sure, usually concluding Allāhu a’lam “God is the most knowing,” which is like saying “Only God knows for sure.”

Nathan: If the majority of Muslims do not understand the Qur’an or know what it says, what is the basis of their beliefs? Where does the Friday sermon material come from? From a Christian point of view it is confusing how a text based faith can operate when people don’t understand the text. With a few exceptions, even in less literate times and places of Christianity, literate people read the Bible to less literate people and less literate people were taught the Bible stories about Jesus orally and through pictures. If the life and teachings of Muhammad does not occupy the same space in Islamic life that the life and teachings of Jesus does in Christian life, what does?

Phillip: Well again here I think there is much more similarity than there might seem at first. Friday sermons are a mixed bag, really, depending on the Imam, but Qur’anic readings and interpretation, followed by stories about Muḥammad and other heroes of the faith are quite common. In communities whose native language(s) is/are something other than Arabic, these homilies are given in the native language. So I think it’s inaccurate to say that Muslims don’t know any of this. I think a good analogy would be, say, someone in a church where the King James Version is used – the language and idiom will be unfamiliar, at least in many places. More fundamentally, though, I would argue that the question of “what the Bible says” or “what the Qur’an says” is always and inherently interpretive. Muslims vary, just as Christians do, in terms of how much of their sacred text they have memorized, are familiar with, can explain, etc. Christians have of course heard biblical stories and passages read to them, and interpreted for them, throughout history. I think, however, that the suggestion that Christians throughout history have had a lot of familiarity with the sacred texts is a mischaracterization. In fact, the average Christian in Europe in, say, the 11th century AD couldn’t have probably quoted an entire verse (as they would have heard the Bible exclusively in Latin, and relatively few understood Latin). Now, Muslims have heard the Qur’an and various stories of heroes of the faith as well. Christians’ understanding of the biblical texts have always been shaped by their communities of faith, and their interpretations are determined to a large degree by those that are proclaimed in their communities. Few Christians, modern or pre-modern, have the necessary tools and knowledge base to really study the biblical texts in their historical contexts in the way that would be necessary if one wants to really answer these questions. Rather, they are instructed in interpretive traditions. The same occurs in Islam. With all due respect, I think it’s a bit arrogant in our assumption that Christians “know” what their texts mean and teach, whereas Muslims either don’t, or are just taught traditions. Much, if not all, of what Christians “know” about the Bible was decided by councils, theologians, and scholars. It’s inaccurate I think to suggest that Christians who have memorized Bible verses, or attend church frequently and can recite stories in colloquial English, “know” them in some absolute sense. They know how it’s translated and the predominant interpretations in the traditions of which they are a part. The same thing is also true for Jews – religious Jews read from their texts daily, but their interpretations of them are bound by the various commentaries and discussions that have been transmitted since the early 3rd century AD (beginning in 200AD with the Mishnah). Christians are often I think led to a false sense of understanding because of the preponderance of translations into colloquial English.

Nathan: As you know, I recently read the Qur’an for the first time – or at least an English translation – and did a book report on it. I have heard that you can’t really understand the Qur’an without being well-versed in Arabic. What are your thoughts on this? The Bible is written in Greek, Hebrew, and Aramaic, but Christians don’t tell people that they can’t really understand the Bible without being proficient in the Biblical languages. What is the difference here? Proficiency in the Biblical languages can add depths of meaning and insight to someone’s understanding of a text, but only on rare occasions does it change the entire message or meaning – and those are typically in situations where someone has a poor translation. What, if any, is the difference with Arabic and the Qur’an?

Phillip: Well in terms of Islamic doctrine, the notion that the Qur’an is only really the Qur’an when one recites it in Arabic has to do with the fact that it is viewed as literally the words of God – God spoke in Arabic, in a perfect way, and there is literally a heavenly Qur’an in Arabic. So Muslims recite the Qur’an in Arabic, and pray in Arabic (praying involves recitation of the Qur’an), and even translations will often be called “The meaning of the Holy Qur’an” or something like that, because they don’t believe that it’s the Qur’an if it’s in any other language. The closest Christianity has come is official translations that served as the only Bible for a church (Latin Vulgate for the Catholic Church, only relatively recently softened). In fact, Bible translation was for centuries punishable by death, and many of the early translators of the Bible into English were put to death. But I’d like to push back a bit on the notion that understanding original languages isn’t that crucial. I think it depends again on what we mean by “understand the Bible.” If by that we mean understand it in a historical context, then it absolutely does matter. One can’t claim to really understand the issues involved with interpreting, say, Paul in a 1st century context without being able to competently deal with his letters in Greek. However, if what we mean by understand here is understanding a set of beliefs, or getting personal meaning from a daily reading, then I absolutely agree one needn’t know Hebrew or Greek. In many ways I think it’s particularly difficult for Protestant Christians to sort of get the perspective of a Muslim because Protestants (and I am by tradition one of them) tell themselves that they decide for themselves what the Bible means, etc. I don’t think that’s defensible; in fact most of what Protestants believe about the Bible is tradition. So ultimately, though there is a difference in terms of language ideology (Arabic, for Muslims, is the language of the Qur’an, and anything else is just an interpretation, whereas for most Christians this isn’t the case (though some still do – King James only Christians are still around!)) I think all traditions are essentially operating the same way. The sacred text is filtered through the traditions and orthodoxy that were subsequently set down. What we “know” or “understand” of these texts is by and large set for us.

Nathan: Without knowing anything else about history, what do you think I would see differently if I could read the Qur’an in Arabic?

Phillip: Well I’m not sure that a whole lot would necessarily change if you could all of a sudden read it in Arabic. I think the more important thing would be whether you were open to all possible readings in Arabic. Much like those who learn Hebrew and Greek in Christian circles, those who are still absolutely committed to the Bible “saying” exactly what they already believed it to say find nothing new. Rather, if one is open to what are historically and linguistically possible interpretations of the text, one would see just how much is possible and simultaneously how little we can say definitively about anything.

Nathan: What is Sharia Law and what is its relationship to the Qur’an? What is its relationship with Islamic life?

Phillip: Well this is probably worth a whole interview in itself, and it’s absolutely not my area of expertise, so I’ll just offer a few comments that I think are probably safe. Sharia law isn’t exactly a set thing; rather, it is a body of legal rulings by scholars and jurists, beginning in the first centuries of Islam. The basis for Sharia was of course the Qur’an, but also the Ḥadith (recorded sayings of Muḥammad), as well as other sources, such as logic and philosophy (the “Classical” period of Islam, in the Abbasid period ~750-1258AD, in Baghdad, was incredibly cosmopolitan. They were translating Aristotle and working on Algebra). Now, there were four main legal schools (Hanafiyyah, Malikiyya, Shafiyya, and Hanbaliyya). It’s generally true that these four schools typically agreed when the Qur’an or the Ḥadith explicitly commented on a topic, but they differed when these sources were silent. The jurists during this period developed the complex sets of laws and interpretive traditions that govern society. Most countries that are predominantly Muslim, from Indonesia to Tunisia, claim that the government rests on Sharia, but the actual manifestation is radically different. Without getting into some of the modern movements, like the Salafis and Wahhabis, it’s important to note that Saudi Arabia represents a different ideology and interpretation of Sharia than, say, Indonesia. The oppressive governments that have held sway in the Middle East since the fall of the Ottoman Empire have stymied much of the previous debate on a socio-political scale (and it had already been under the Ottomans before them). It would be instructive to see the ways in which these debates have shapes public life in Indonesia. A solid work on the topic of Sharia and its development is Noah Feldman’s “The Fall and Rise of the Islamic State” (Princeton University Press, 2008). He outlines how the “Classical Islamic Constitution,” much like our own, was based on a system of checks and balances between the executive and the schools of Islamic scholars and jurists. He further argues that the unfolding of the modern period has essentially destroyed the prospect of a return to the classical system. I’m not sure such pessimism is totally warranted, but I agree it would require a great deal of change to make it happen.

Nathan: From your studies and experience, is opposition to Sharia Law considered opposition to Islam, or even religious persecution/discrimination from an Islamic perspective?

Phillip: I think speaking abstractly that if you walked up to someone and said “I oppose Sharia law,” that would be considered opposition to Islam. But within the Islamic tradition, I think it would be accurate to say that there was historically, and has been quite recently, much debate over the specifics of Sharia, what it means to govern according to Sharia law, and its role in public life. The notion, current in certain circles in America, that Muslims are trying to impose Sharia law on America, is I think bogus. This has spurred a number of groups to propose anti-Sharia law amendments to their states’ constitutions, the effect of which is almost solely to remind local Muslims that their way of life is seen as incompatible with America, etc. On a broader level, I think it is quite easy for things like Sharia or the Qur’an to become symbols in the fight over competing views of society, religion, etc. Given the prevailing discourse in the US, these symbols have become emblematic for many Muslims of the discrimination they experience.

Nathan: If more Americans were open to Sharia, what do you think Muslim communities would appreciate being able to change about the laws in the areas where they live? In other words, are there specific restrictions or freedoms that would be granted by Sharia law that Muslims long to see in their communities? Do you see this as even being a felt desire for Muslim communities?

Phillip: I can’t say that, in my experiences with American Muslim communities, I’ve gotten any sense of a desire to have any added restrictions or freedoms they don’t already enjoy. Here again it’s important to note that American Muslims are extremely diverse (ethnically, politically, culturally, “religiously”), and you’d probably find just about every possible answer to a question like, “How does (your understanding of) Sharia fit in with your life as an America?” I think most American Muslims would probably say they attempt to live by their understanding of what Sharia law is. What they mean by that if pressed for particulars would probably be (has been, in my experience) quite different. Again, Sharia is a very complex set of principles, legal rulings, practices, etc. Most of them don’t have much relevance for contemporary life, especially in 21st century America. I think Sharia is, in many ways, more a symbol of a way of life, set of beliefs, etc. that stands, in many Muslims’ minds (both American and otherwise), for their faith, their values, etc. That’s the real power in many of these concepts. Most Americans have no idea what Sharia law actually is, but that hasn’t stopped it from becoming a convenient symbol used in Islamaphobic attacks. The fact that many Americans see “creeping Sharia” in things like the opening of a local mosque, and then propose anti-Sharia amendments to their state constitutions, illustrates this perfectly. I think, more than anything else I’ve taken away from my conversations with American Muslim communities, I’ve taken away the idea that they want to be free to practice their faith without being considered un-American. I think, for the overwhelming majority of American Muslims, that would be more than sufficient.

Nathan: From my reading of the Qur’an, it appears that Muhammad owned slaves, took slaves in battle, including sex slaves, had multiple wives, taught that women were of lesser value than men, mutilated people, decapitated people, killed people for religious differences, and possibly even crucified people. Am I reading this correctly? Historically, do we know if these things are true?

Phillip: Well as I mentioned previously in our discussion, our knowledge of Muḥammad’s life comes almost exclusively from later histories whose source material is of dubious historical nature. So in the western tradition of the writing of history, I’d say we have very little to go on, and much of the tradition is almost certainly later creation. It is true that, just like in the Christian world of the sixth and seventh centuries AD, Muḥammad (and other peers) practiced various forms of slavery, polygamy, etc. Slavery, after all, was a normal part of life, and had been divinely sanctioned in the Bible (Exodus 21:1-11, Leviticus 25:44). The Bible contains discussion of female slaves who could be kept enslaved if they pleased their masters (almost certainly, IMO, referring to sexual slavery). Both slavery and polygamy served important economic and social roles in the ancient near east and the world of late antiquity. It is interesting to note that, according to tradition, many of Muḥammad’s marriages were to women who otherwise had little economic potential, including widows who had few possessions, etc. Polygamy is only allowed if a man can treat each woman equally. Women in the early Islamic community played important public roles (check out Aisha’s life), and tradition narrates heroic deeds by women Muslims in battle. Muḥammad is said to have spent a lot of time with his wives, enjoyed their company, and taken their advice in important matters (Umm Salamah helped him stop a mutiny). As far as slavery is concerned, in the context of contemporary Byzantine Christianity, Islam actually seems to have been quite progressive. Slaves were considered equal to free men in terms of their standing before God, and numerous verses in the Qur’an encourage the emancipation of slaves (see, e.g., 90:13). Muḥammad is said to have been responsible for freeing over 39,000 slaves (including several mass emancipations by his followers at his order). I’m not quite sure what you mean when you say Muhammad taught women were “of lesser value than men,” but for the time, again Islam was actually quite progressive. Women were granted many rights they had not enjoyed previously (and in the west wouldn’t enjoy until the late 19th century): Islamic law emphasizes the contractual nature of marriage, requiring that a dowry be paid to the woman rather than to her family, and guaranteeing women’s rights of inheritance and to own and manage property. Women were also granted the right to live in the matrimonial home and receive financial maintenance during marriage and a waiting period following death and divorce. Muḥammad even appointed one woman, named Umm Waraqah, as Imam over her household. With both of these issues, I think it’s important to distinguish between the ideals espoused in the Qur’an and Islam jurisprudence, and wider cultural norms that were often much harsher, and much more explicitly patriarchal. In the same way Christianity has been plagued by the tendency of its adherents to import accepted cultural norms (often explicitly banned in the Bible) into its practice, Islam can I think fairly be said to suffer from the same. Finally, as for battles, killing, etc., these things were all parts of contemporary life, and not viewed as immoral at the time. They are a part of the Jewish and Christian sacred texts. Even in these cases, though, the Qur’anic prescriptions, and the traditions of the prophet were much more progressive than contemporary societies (including the Christian Byzantine and European polities that followed).

There is no doubt and no denying that violence, slavery, etc. were parts of the early Islamic community. They were parts of Israelite life, and slavery as an institution continued until, as we all know, very recently. I think from a purely historical perspective I find it odd that aspects of society that were absolutely not considered immoral (as they are today) are treated as if they are signs of immorality, especially when people discuss Islam. Slavery is divinely sanctioned in the Bible, and yet few Christians consider the God of the Bible immoral, or talk about this fact as a reason to consider Judaism an immoral religion. Yet we do with Islam.

Nathan: What obstacles, if any, do these actions of Muhammad pose to Muslims in seeing these things as immoral? On what basis would a Muslim deem these actions or activities immoral?

Phillip: Well here is where I would say that they pose the same problem that the violent nature of many of our sacred stories poses obstacles to us. Throughout our history as the Church, Christians have taken inspiration from the stories of God as a warrior, divinely sanctioning institutions such as slavery, etc. The American Christian who argued that owning slaves was part of the divine plan for creation could, with full justification I argue, base that belief on the biblical texts. There are many Christians who feel justified using violence, or at least supporting the use of violence by others “on our side,” based on their readings of the biblical texts. There are relatively few pacifists among American Christians. In the same way, the traditions associated with Muhammad and the early Islamic community certainly provide material for those who lean toward using violence, extremist ideology, etc. There is much in both traditions, however, that counters these messages. I am fairly convinced that people find what they want in many of these texts. The question facing each Muslim (and Christian, and Jew) individually, and each community, is what ideals will he/she/it uphold, and what aspects of its past and traditions belong to the world today, and what needs to be jettisoned. There is much in the actions of Muḥammad and the early Islamic community that can tie tradition to what I would say is positive progress. There is also much that can run counter to the trends of much of the rest of the world. It’s likely that people who tend toward both trajectories will adopt the portions of Islamic traditions that support each trajectory.

Nathan: Is Muhammad the moral exemplar for Muslims the same way that Jesus is for Christians? In other words, do Muslims seek to pattern their life after the life and teachings of Muhammad the same way that Christians, though not perfectly, aspire to pattern their life after the life and teachings of Jesus? For me, I think I approached reading the Qur’an the same way I approach reading the Gospels (“What is Jesus doing, what is he saying, how do I apply this to my life?”) and I wonder if this is appropriate?

Phillip: Great, great question, and, if you’ll forgive me, I would like to devote a bit of space to discussing it. The simple answer is, yes, Muslims view Muḥammad as the quintessential Muslim, to be emulated. In addition to the story (sira) of his life, his sayings and pronouncements were collected, and there was a canonization process of sorts to determine which of these remembered sayings were genuine. The result was a collection of sayings and actions of Muḥammad that is called the Ḥadith. While not considered as authoritative as the Qur’an, these are often some of the most quoted of all Islamic traditions by Muslims.

What’s important to flesh out is what that means in practice. As people who aren’t in the early Islamic community, the question that presents itself is “what does it mean to emulate Muḥammad?” This is the same question that comes up when one asks what it means to follow the Qur’an. And of course, just as I mentioned when discussing the Qur’an and Muslims’ understanding of it, Muslims understand the legacy of Muḥammad in different ways, through the lens of interpretive traditions. Muslim theologians, scholars, and jurists have devoted much attention to understanding Muḥammad’s life, and how to appropriate his actions and sayings for current communities. The ways in which Muḥammad’s legacy was appropriated legally for the Islamic community (Ummah) was of course also the domain of the scholars and jurists mentioned above. The moral implications/practical implications have been worked out in communities from the very beginning. There has been much diversity that, also like diversity of Qur’anic interpretation, has been stymied for the same reasons I mentioned before. Still, a love of diversity actually exists, and (contrary to the portrait common in the media), there have been quite a lot of condemnations of ISIS, al-Qaeda, etc. and their actions by Muslims, including conservative Muslim scholars, over the past decade and a half. These rarely garner much attention in America, I believe because they complicate the narrative that serves the interest of those in power.

I’d like to draw parallels that I think exist but that might not be clear to the reader. Christians have the same diversity of traditions that govern the ways in which Jesus’ life and teachings are appropriated for contemporary society. To what degree must one emulate Jesus’ life? Must one be unmarried? Many Christians throughout history have argued that such a step is necessary to truly follow Jesus, while more and more Christians have argued that such drastic steps are not really at the heart of Jesus’ message (despite the fact that Paul also specifically adjures Christians to marry only in cases where they are unable to control their sexual impulses). Must we shun worldly possessions? In a number of places Jesus suggests that one’s possessions present an almost insurmountable obstacle to true obedience to God, and recommends giving all possessions away to the “rich, young” ruler (Mark 10:17-22), but most Christians today moralize this in a general way and argue that the real point is that we should work to make sure we don’t let it rule our lives. The Sermon on the Mount (Matt 5-7), or Luke’s alternative version, the Sermon on the Plain (Luke 6ff), contains some fairly radical instructions, which, despite common interpretive traditions, I don’t see as being hyperbole, yet few Christians today seem to feel obliged to, say, pray for their enemies and avoid striking back regardless of what they do. How many Christians in the US denounced intervention in Iraq or Afghanistan after 9/11? Do we really believe, as Jesus suggested, that if we don’t serve the homeless, poor, hungry, etc. then we will be cast into eternal punishment (Matt 25: 41-46)? Homelessness is a big problem in the US, and though charities exist – both faith-based and secular – how common is it for people to leave church and drive by these people on the streets without even batting an eye. There are many more issues here, but I hope this small sample is enough to provoke some thought. Whether we want to admit it or not, we all have ways of appropriating the legacy of the pillars of our faiths, and no one literally follows and emulates every thing that is modeled or commanded by the founder or most important figure in one’s faith. So again here, just as Christians have historically, and are contemporarily characterized by great diversity in terms of what they believe, and how they approach the topic of what it means to follow Jesus, Muslims are as well quite diverse in practice.

Much is cultural, too. For example, in Jordan there is no law in terms of female dress, or whether women have to cover their heads, etc. There are Muslim families whose daughters don’t cover their heads at all, others cover their heads but not their faces (with a head scarf we call the ḥijab), while others cover their bodies, heads and faces except for their eyes in black garments (which we call the niqab). (Aside: the burqu’ “burka,” is different still, covering even the eyes with a material through which one can see out, but which obscures even the eyes to those looking in. It’s usually blue, and is mostly found in Afghanistan and Pakistan). The Qur’an simply admonishes women to dress modestly in loose clothing, covering their heads (which, at least in ancient Arabia, was something men did as well), but there is nothing about covering their face or hands. Our earliest sources actually suggest that covering the face, as well as the separation of women into a separate ḥarim, was learned from the Byzantine Christians! Many cultures around the world have traditionally insisted on their women covering their heads, faces, etc., and as Islam spread to many of them, patriarchal tendencies extended this notion of conservative dress to the traditional practices of covering the face, hands, etc.

I’d love to say more, but the point that I hope to have made is that while it is true that Muslims look to Muḥammad as an exemplar, morally and socially, it is also true that what that means is just as subject to the interpretive traditions, and communities of which people are a part, as Qur’anic interpretation has been. The same has been true, and still is true, for Christian communities with regard to how we appropriate Jesus’ example.

Nathan: Several of our political leaders here in the United States have said that Islam is a religion of peace. Based on the Muslim people I know, I would have to agree with them. Some of the most kind, hard working, and hospitable people that I have ever met are Muslim, particularly the Muslim refugees I have gotten to meet over the last few years. However, it seems like our news is almost monthly covering some tragedy or atrocity committed in the name of Allah. As you know, there are a hundreds of different sects or denominations that fall under the broad religious category of “Christian.” Can these differences that I see between the Muslims I know and the ones that are on the news be explained in this way? Are there “denominations” in Islam that more reflect a religion of peace and others that reflect a religion of violence and oppression?

Phillip: Well I have to say I don’t really think that a particular religion can be characterized as one or the other (i.e., as “peaceful” or “violent”). How would we decide? I mean, if we restrict it to the texts that each has considered as sacred, then all three Abrahamic faiths have a bit of each. If we look at the actions of those people throughout history who have claimed each faith, which I think is the only really objective way of even trying to get at this kind of question, we would find the same – Christians, Jews, and Muslims have been (and continue to be) both incredibly peaceful and abhorrently violent toward each other. Unfortunately, the language and symbols of religion can be used as mechanisms for tying a particular social or political cause to the message of a religion. In our own history as Americans, we can find example after example of this phenomenon. The early settlers often quoted scripture from Exodus and Joshua to frame their conviction that God had liberated them and were leading them to a promised land, which they were to Christianize (they appealed to God’s sanctioning of genocide against the unbelieving Canaanites as justification for genocide of native communities). Far and away the largest group of Jewish settlers perpetrating violence in the West Bank are ultra-orthodox, who believe they are re-taking the promised land, and, just like the Israelites in the Hebrew Bible, are fully justified using any means necessary.

For Muslims in the Middle East, much discourse has revolved around the cultural and political ailments form which their societies have suffered for the past centuries. For a while, politicians championed the notion of pan-Arabism as a way of improving the plight of the Arab countries, with figures such as Gamal Abd an-Nasser and Hafez Al-Asad talking more about Arabism and culture unity than Islam. With the failure of the pan-Arabism movement to produce meaningful change, more and more Arabs have focused on the religion of Islam as the one thing that could unite and change their circumstances.

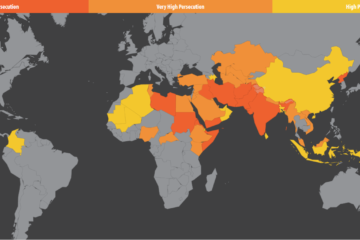

Now I think perhaps the key to understanding the spread of a rigid extremist ideology in the Middle East and N. Africa the past half century or so is the role of Saudi Arabia in spreading it. Saudi for decades funded Imams and curricula that have taught a rigid and intolerant (Wahhabi) brand of Islam, which downplays diversity of opinion in favor of strict adherence to supposed fundamentals of the faith. In fact, Saudi Arabia, along with Qatar, is still one of the largest financiers of terrorist groups, especially ISIS. Interestingly, as Fareed Zakaria has recently noted (https://fareedzakaria.com/2016/04/21/saudi-arabia-the-devil-we-know/), Saudi Arabia has been a target of the very fundamentalist intolerance that it has (and continues to) spread, as evidenced by Al-Qaeda’s mission to overthrow the Saudi family, which is seen as too corrupted by the west. Zakaria notes that in 1950 less than 1% of Muslims in the Middle East espoused a Wahhabi ideology; now it is by far and away the majority, at least among Imams. This is almost solely thanks to the Saudi mission. It has stamped out a lot of the diversity and plurality that existed within Islam in the region. Combine that with the political oppression and low socio-economic circumstances in which most in the region find themselves, and you have a dangerous recipe. It’s really impossible to overestimate just how effective, and landscape changing, this fundamentalist/extremist spread of ideology has been. Many Muslims today are not even aware of earlier diversity in Islamic interpretation and traditions, and, much like Christian and Jewish fundamentalists, would probably see such diversity as something like relativism, or something which would lead to decay. I emphasize again, however, that this is the case for the Middle East and N. Africa, home to only about 25-30% of the world’s Muslims (Saudi Arabia represents only 1% of worldwide Muslims!!!). This is my problem with the notion that what happens there represents the religion. It also poses a problem for terminology; how many times do we use phrases like “The Muslim world” with reference to the Middle East. There is, in reality, no “Muslim world.” Muslims inhabit most countries, and are as diverse as Christians in terms of their ethnicities, languages, backgrounds, and political opinions. Just as we don’t speak of the “Christian world” when we talk about America, or the west, we need to stop generalizing ME/NA issues to all Muslims worldwide. We’ve also got to start contextualizing the issues that drive violence in the Middle East, and even how religion is playing a role in the competing rhetoric in that region, and separate that from a discussion of Islam in general. Persisting in generalizations and simple correlations is certainly easier, but it isn’t very accurate or helpful.

Nathan: If you were going to put a three-person panel together of experts who taken together would be most able to give their audience an accurate understanding of Islam and its place in the world today, who would you choose and why? I am assuming you would choose people who could speak from different points on the political and theological spectrum.

Phillip: This might be the most difficult question to answer. Again, as someone who is not a specialist in Islamic religious sciences, I’m not sure I am qualified to pick scholars who would fulfill the criterion you listed. Still, I’ll give it my best shot. First, I’d probably choose Fareed Zakaria (CNN journalist). He is an Indian-born Muslim, though he hasn’t practiced for quite some time. One reason is that Fareed understands the issues that many traditionally Muslim countries, especially in the ME/NA, are facing, and represents a moderate voice. His specialty (he has a PhD from Harvard) is in international affairs. Now, it might seem strange to choose a non-practicing Muslim. His own personal philosophy and faith perspective aside, I think he is extremely capable of separating and contextualizing issues in a way that is helpful and balanced. He is probably the most thoughtful voice on these issues on TV, or even in the press in general, and I think would be extremely interesting for most people to hear (I highly recommend his weekend show, GPS, which usually begins with a diatribe on an issue that is both concise and incisive). Second, I would choose the Islamic scholar Akbar S. Ahmed, the Ibn Khaldun Professor of Islamic Studies at the American University, a progressive scholar of Islam. Ahmed was born in Pakistan, studied at SOAS (Univ. of London), and has been an outspoken critic of the extremist ideology that permeates so much of the ME/NA. He has participated in interfaith conferences and discussions, and is an outspoken proponent of such dialogue as the only way to live in peace in the modern world. I think he would be considered a “liberal” Muslim voice. Finally, I would choose the current Grand Mufti of Egypt, one of the most prestigious religious figures for Muslims across the world, Sheikh Shawki Allam. Allam is fairly considered a conservative (though not fanatical). He is also a Sufi (it is important that Sunnis or Shias can be Sufis – they aren’t mutually exclusive). Voices and positions like his will be important for reversing the tide of extremism.

Unfortunately not all positions and perspectives can be represented, but I think this would be an interesting panel and give a really good idea of the diversity of Islam, the issues facing Muslims in parts of the world that most in the audience would be ignorant of, and accurately represent worldwide Islamic diversity than is presented in the media.

Nathan: Phillip, one of the things that I try to encourage people to do, and am trying to grow in myself, is to see people as people and not as a representatives of a group – e.g. “white,” “black,” “female,” “male,” “Christian,” “Muslim,” etc. I think our human brains want to see those of our in-group as unique individuals with character, values, and personalities unique to the individual, while seeing anyone that is “other” as a representation of our ideas about that “other” group and not as an individual. Are there any stories or insights you have gained from your experiences or studies that you think could help a predominantly American, predominantly Christian audience see Muslim people as people and not whatever it is they might associate with “Islam?”

Phillip: Well first, I absolutely agree that human brains are predisposed to put things into groups and patterns. We don’t do well at all with grays, but I think most people can relate to the notion that most of life is in the gray areas. I think this is why there is such a strong tendency to think of whole religions, with millions or billions of followers worldwide, as characterizable as “peaceful” or “violent,” or as any one thing. I think the only way to truly get past these kinds of generalizations is to spend time with members of different groups and communities than one’s own. I first lived in the Middle East when I was 10 years old. I went back frequently, and lived there again while I earned my M.A. from the University of Jordan. During all my time there, I gained so many friends, had so many positive (and some negative!) experiences, and gained the ability to see the world through others’ eyes (though admittedly imperfectly). I didn’t love everything. That wouldn’t be “real” either – people who come back from an experience anywhere and proclaim their unqualified love of a place probably didn’t spend much time there. But humans are, ultimately, relational people. I think the best advice I can give to people is to reach out and take the trouble to get to know Muslims in your communities. Go visit a mosque. Listen to the Friday khuṭba “sermon,” or, a personal favorite, go have an ifṭar meal during Ramadan. Let them tell you what they believe, how they feel about current events or issues, and how they go about interpreting and appropriating their traditions. They’ll probably be so happy you’re there that they’ll spend more time than you’d want them to.

Nathan: Thank you so much for doing this with me Phillip! I think you’ve given everyone who reads this a lot to think about, including me. I don’t think we can “wage peace” effectively in our world without diving into the tough questions and I’m grateful for getting to explore these things with you.

Phillip: Thanks for having me! I completely agree and hope that something I’ve written provides an opportunity to continue the discussion. Let me end with a reaffirmation of something that I’m sure came through loud and clear to the reader: I really believe we have to stop thinking in terms of “Islam” or “Christianity” is a certain thing, or that a certain sacred text says or means a certain thing. All of these sacred texts are complicated, and people understand them through traditions of interpretation that have been developing for centuries, as well as through their own set of experiences. Just as humans combine peaceful and violence impulses, the capacity to love and hate, a tendency toward inclusion as well as prejudice, so these traditions will be used as rhetoric supporting all of these things. Rather than treating a whole religion as a monolithic entity, with its own ontological reality, I think we have to get back to treating other humans, as we want to be treated ourselves. The more we get to know Muslims (and others in general), the more we will realize that all of these issues are really lived out in shades of gray. Dualistic, black and white thinking, as you noted, is our nature, but only contributes to our problems.